Ghosts and the Great Novels of War

The Literature of Army Writers and America's Sense of Self. Part IX: Matt Gallagher

“Almost a decade after the first bombs were dropped in Afghanistan, even the most avid bookworm would be hard-pressed to identify a war novel that could be considered definitive of this new generation's battles.”

-Matt Gallagher, “Where's the Great Novel About the War on Terror?”, June 14, 2011

Close to 15 years ago, Matt Gallagher asked why the Global War on Terror (GWOT) produced a great wealth of non-fiction memoirs and books, but no defining pieces of fiction. Was it a function of time, as maybe the definitive novel just needed a certain amount of distance from the wars to gestate? Or was it because the wars were too messy, sprawling, and, well, “forever” to capture with any degree of comprehensiveness? Or perhaps it was because the wars were too distant–viscerally immediate for a small fraction of the population, but abstract affairs for most? At the time, none of these explanations seemed satisfactory.

I did not know Matt in 2011, but I see in this line of inquiry–and I may be reading in my own feelings–a desire to explore GWOT’s story as understood from the perspective of the broad American public. What did the wars mean to them? What were the storylines? Who were the characters and what were the plot lines? When war fiction catches fire, it illuminates answers to these questions. Even if all we glimpse are partial answers, such shadows of truth are preferable to wondering whether any stories had even registered with Americans; wondering, in essence, whether the wars meant anything at all to our people?

Much later than Matt, I tried to answer these questions with public opinion research. At the time, I was leading a research nonprofit focused on reducing polarization. We launched a series of public surveys that asked Americans not just how they felt about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but about the narratives they held regarding these conflicts.

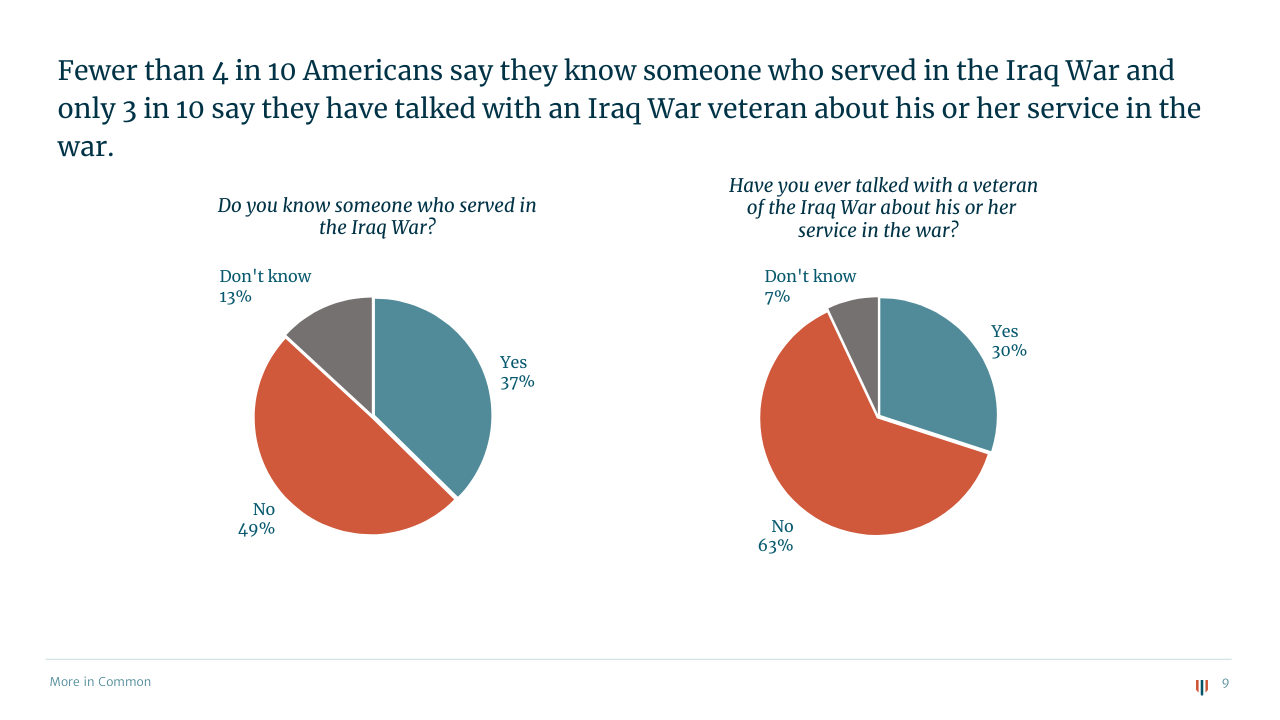

We asked, for example, about proximity to the conflicts. Did they know someone who served in the Iraq War? Had they ever talked with an Iraq War veteran about his or her service in the war? The most common response to both questions was “No”.

Source: The Veterans and Citizens Initiative.

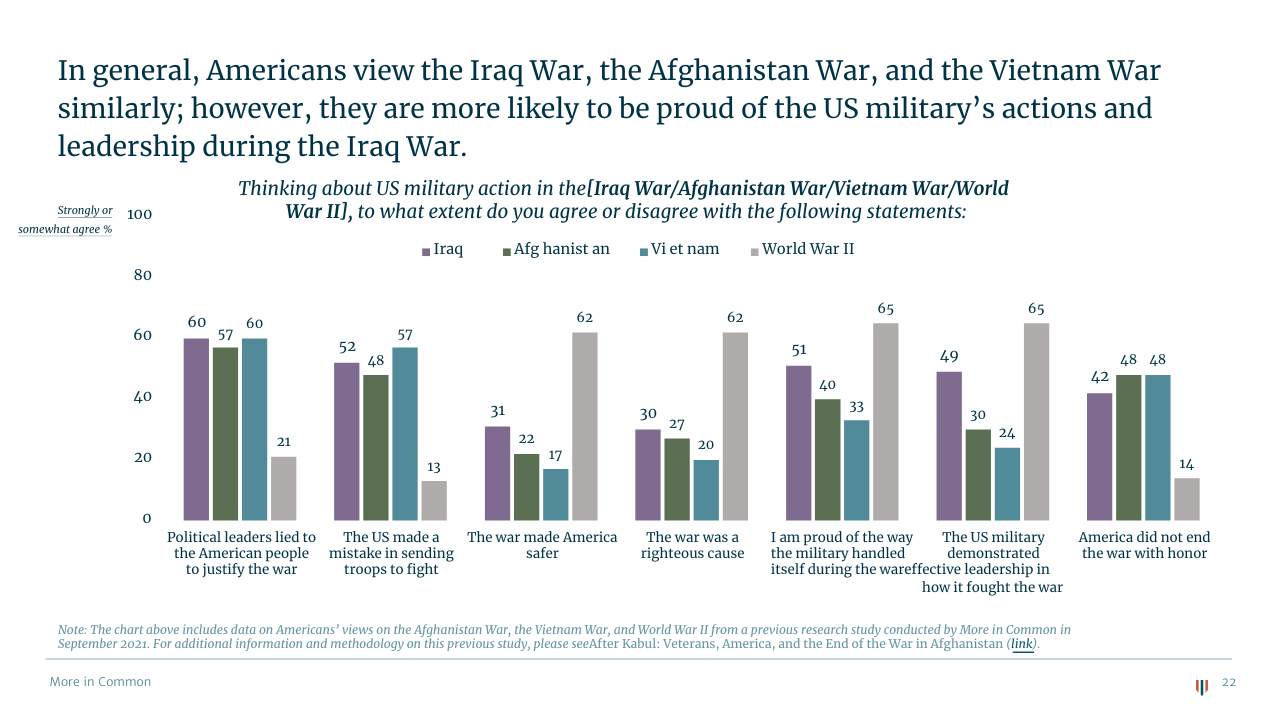

We also asked Americans to compare and contrast GWOT (the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan) with two other wars that loom large in the American mind: the Vietnam War and World War II. As the graphic below shows, GWOT was seen as much more similar to Vietnam than World War II.

Source: The Veterans and Citizens Initiative.

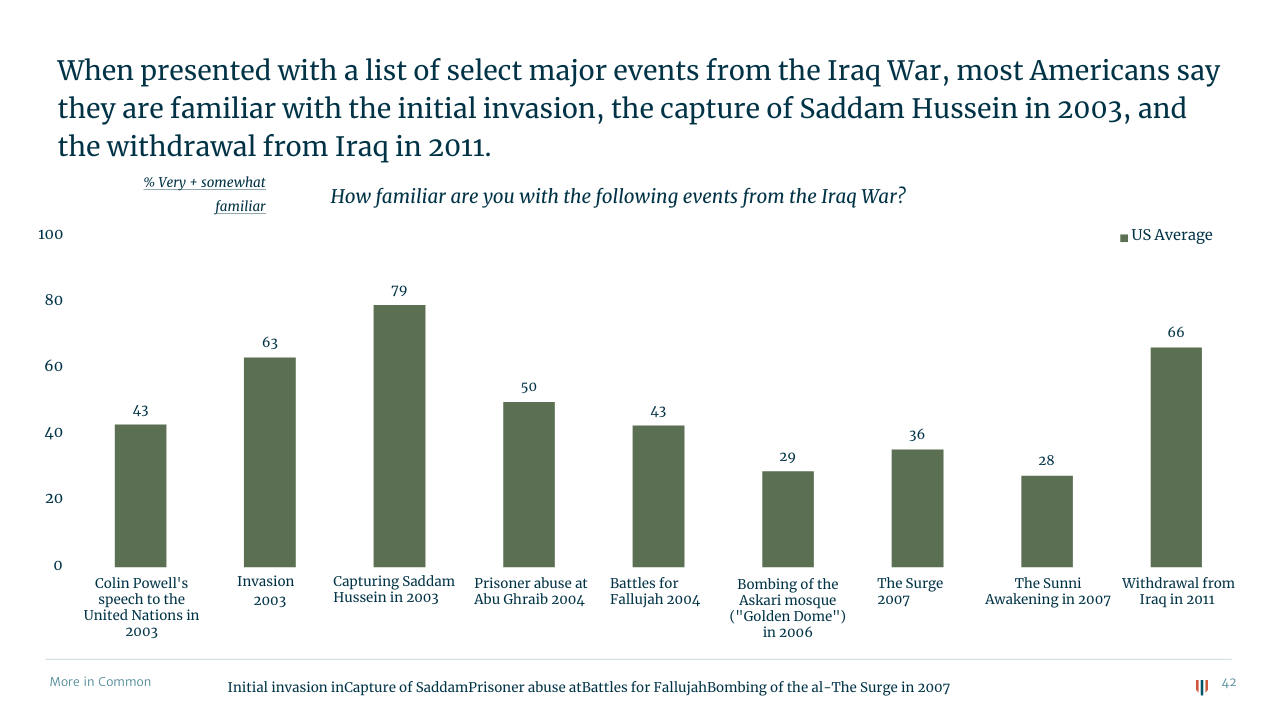

And we probed people’s memories to see which events from the wars stood out. As this chart shows, with the Iraq War, the initial invasion, the capture of Saddam Hussein, and the withdrawal all had much greater levels of familiarity than even major strategic developments like “The Surge” of 2007.

Source: The Veterans and Citizens Initiative.

These studies never provided any sort of comprehensive answer to the question Matt asked in 2011 or to the underlying questions of meaning that first animated my research, but they showed that stories exist. The narratives might be vague and disjointed in many respects, but even in 2022 when I was doing this research, people held strong memories and impressions of GWOT.

Rather than using public opinion research, Matt answered his own question through storytelling. As an author, editor, reporter, and teacher, Matt has produced some of the most definitive works of GWOT fiction and nonfiction. He has also helped elevate the broader military writing community, enabling the American public to hear more voices from the GWOT generation (as well as voices from older and younger military generations).

Matt’s first book, Kaboom: Embracing the Suck in a Savage Little War, was published in 2010 and was an immediate hit with the military community and broader public. The book was based on the blog then-Lieutenant Gallagher maintained while leading a platoon, the Gravediggers, on a fifteen month tour in Iraq (2007-2009). Though the blog was eventually shut down by the Pentagon, Matt’s book took Americans into the platoon-level experience in Iraq. It was heralded by veteran military authors such as Bing West, who wrote, “He [Gallagher] is also your classic mud grunt, disdainful of staffs, suspicious of outsiders, bemused by the eccentricities of higher headquarters ("we found ourselves playing dance, monkey, dance") and angered by any Iraqi or American who is mendacious, clueless or lazy.”

Source: Matt Gallagher.

In 2013, Matt, along with Roy Scranton, edited Fire and Forget: Short Stories from the Long War. This work featured military writers such as Phil Klay, Colby Buzzell, and Siobhan Fallon (whose work and story we featured in an earlier Army 250 post). As one of the first such compilations, Fire and Forget helped cohere the GWOT writer community–in the closing section of the Preface, the editors wrote: “Truth, truthiness, in this mass media cacophony we live in comes up something for grabs. Well, here’s some. Grab it. We were there. This is what we saw. This is how it felt. And we’re here to say, it’s not like you heard in the stories.” Truthiness continues to be up for grabs, but this anthology helped bring many more lived experiences and perspectives into the mix.

Source: Matt Gallagher.

Finally, In 2016, Matt wrote a GWOT war novel, Youngblood: A Novel. Set in Iraq as America withdraws, Youngblood earned widespread praise. Tim O’Brien, whose own The Things They Carried remains one of the definitive books from Vietnam, said, “"Youngblood is not only a 'war novel,' it is a rich, fully formed, and beautifully executed novel-novel, way beyond the chicken coops of genre, a novel about the human heart in contest with itself, a novel about memory and longing and grief and hope and guilt and late-night ironies that raise a chuckle to the lips of the dead.”

Source: Matt Gallagher.

Matt graciously agreed to be interviewed for Army 250. What follows is a lightly-edited version of our e-mail correspondence.

You’ve talked about how the experience of having your Iraq War blog shut down motivated you to tell the story that eventually became Kaboom, but had writing always been a passion or interest of yours?

Writing and reading were ubiquitous elements in my life long before I thought about writing myself. The biggest room in my childhood home was my mom’s library, and she taught my brother and me early that reading was a way to learn about life, better appreciate it and enjoy it, all at once. She was new to the west—Reno, Nevada, to be specific—so she read Joan Didion and Robert Laxalt. She admired Tom Wolfe but found his depiction of Virginia women in one of his novels off and wrote him a letter saying so. He wrote back, allowing that she might have a point.

Some books I read as a boy that I remember influencing me, even changing the way I thought: The Lord of the Rings trilogy. The Giver. The Chronicles of Narnia. Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. Johnny Tremain. The Martian Chronicles warped my brain in middle school, in the best of ways.

Sometime in 10th grade I gave up the dream of making the NBA and wandered into the office of the high school newspaper. It felt natural because reading was already how I engaged with the world. I didn’t know it then, but I’d found both my tribe and life’s pursuit.

What surprised you most about the reception to Kaboom?

With the blog, I was surprised at how many people who weren’t family or friends ended up reading it. It’s easy as a deployed soldier to feel disconnected from your country, to believe no one cares about the war you’re fighting. And while there was (and is) plenty of truth to those vexations, enough random blog readers showed me, when I needed it most, that many Americans do care about servicemembers and what’s happening on the other side of the globe in their name.

With the book, I got a rapid and forceful education in how some people read to fulfill—rather than challenge—their preconceived notions. One evening, I read a passage from Kaboom in Washington D.C. and had an angry protestor type call me a warmonger for my efforts. Okay. Later that week, I read the same passage in Philadelphia, and had an attendee in the front row say under his breath that I was “A hippie p****.” Which is it? I can be one but not both! So, I learned something obvious, that people often come to the concept of modern war with their own deeply held ideas, and all any writer can do with the subject, particularly a veteran-writer, is tell the hard truths about it, messy ruin, dark absurdity, all the rest, too.

Your first book, Kaboom, stood out for giving voice to the young soldiers of the War on Terror. We’re now more than 20 years out from the invasion of Iraq and I’m curious, how has becoming a parent influenced, if it has, your writing? (On my mind as I ask this is Tim O’Brien’s 2019 book, Dad’s Maybe Book.)

There’s no doubt being a dad to two young boys has influenced how I think about the world, which in turn affects my writing. It’s been over fifteen years since I served in Iraq, yet I still find myself thinking sometimes about the teenage insurgents tasked with taking AK potshots at American soldiers and emplacing roadside bombs under dark’s cover. Were they diehard jihadists? Almost definitely not. They were doing what likely seemed natural to them, furious about the war, their family’s poverty, about their dead or imprisoned fathers and uncles, who knows what else. Most honest American veterans I know would say that would’ve been them, had circumstances been flipped.

Of course, there’s limits to empathy in real life, especially when these teenage insurgents would kill you and your soldiers if given the opportunity. Still. I wonder what the ones who lived are doing now, how they look back on our shared skirmishes and close calls. One of the reasons I cherish literature is it allows for this kind of rumination.

Then there’s the fallen, friends I remember who died in Iraq and Afghanistan at impossibly young ages like 21, 22, 24. They’ll never hold their newborns and be able to tell them the ridiculousness of life is mostly worth it. They’ll never see what’s happening with the new generation and wonder what the hell is going on. They’re missing out on so much. Even though the loss of them is worn now by time the sorrow lingers, deepens.

The question was about parenthood. Would I kill for my sons, to protect them, if I felt I needed to? Yes, no doubt about it. And for that reason, I think I understand why war happens better than I did when I fought in one.

One of the reviews for your most recent novel, Daybreak, categorized the book as “the first great military-inspired novel of this post-Global War on Terror era”. Were you conscious of such a shift, from the GWOT era to a post-GWOT era? Did that at all inform or show up in your writing as you crafted the book?

Sometimes you write stories that take 200, 300 pages, full of nuance and complication and narrative arc, etcetera, and then you see a review that crisply explains what you did in one sentence. This was one of those. Certainly I was aware during my own time in Ukraine, and while writing Daybreak, it was different than what had come before. But it didn’t influence the story much, because I prefer to start with character(s) and build out from there. Yet of course the aftermath of the GWOT seeped into the book, how could it not? So many Western veterans I encountered over there were sifting through the previous two decades, trying to make sense of it and their part in it all. Kabul fell, what, six months before the renewed Russian invasion? Zelensky put out the call for international soldiers willing to fight for Ukraine, those who answered it were, quite often, GWOT veterans, in all shapes, varieties, and experiences. The ghosts of old wars haunt every current one. This was just the example I myself was familiar with.

Wars are different, soldiers are different, but there are often similarities and consistencies. You’ve been an active advocate for and supporter of Ukraine in its defense against Russia’s invasion. In your time with Ukrainian soldiers, how does their experience and outlook compare with your time in Iraq back in 2007-2009?

In some ways, they were quite similar—the everyday courage displayed by young, rough-and-tumble people willing to say, “I’ll go,” because someone has to. The camaraderie I witnessed among the Ukrainians on the squad and platoon levels couldn’t help but bring me back to my time in uniform and on the line. In other ways, though, it was tremendously different. This is an existential fight for Ukraine. They’re not sweating out fifteen months, trying to survive and find some vague string of purpose they can take home with them. It’s victory or ruin, the potential destruction of everything they love and know. That’s hard for American brains to comprehend, I think. I’ve been over there a few times and embedded with various Ukrainian units and it’s still challenging to comprehend, to be honest.

What’s the most memorable interview you’ve ever given? And, is there an interview that you conducted (i.e., interviewed someone else) that stands out in your memory? If you could interview anyone, who would it be?

The most memorable interview I’ve given is easy. (And a shameless humblebrag, so sorry but not sorry.) In 2016, David Petraeus interviewed me in person at the 92Y in Manhattan. He’d read a positive review of my novel Youngblood and reached out over LinkedIn. I thought at first it was college friends of mine screwing with me … anyhow, to have the commanding general of the war I fought in asking about my writing and tour was pretty surreal, considering eight years before my scout platoon and I had pulled very outer security for him and his detail when they came to our rural outpost in Iraq. All the more so because some of my writings over the years have been critical of his counterinsurgency strategy. I’m not a fanboy, I tend to be skeptical of power, but I won’t lie, it was a cool evening.

The most memorable interview I’ve conducted is a tougher one. There’s the grandmother near the Russian border teaching herself Ukrainian at the ripe-old-age of 75 because it’s the only way she can think of to honor her fallen grandson. There’s the Zoom call with a young Afghan woman telling me about her escape plan from Kabul as Taliban patrols roam her neighborhood. There’s Tim O’Brien, who you mentioned earlier, one of our greatest living novelists and clear-eyed chroniclers of American war. There’s Chris Paul, the Hall of Fame-bound point guard, who I interviewed when we were both at Wake Forest and he was just a skinny freshman with ambitions on the starting lineup.

I’ll stop there. Writing’s taken me many weird places and allowed me to meet many fascinating people, something I hope to never stop being grateful for.

My dream interview? George Orwell’s ghost. He saw the political machinations of the postwar world coming and wrote with such clarity and exactness. So many writers these days have nothing to offer but their own musings and contempt for anyone and everything that disagrees. He wasn’t like that. He said what he meant, meant what he said, then lived his principles.

You’re now a writer in-residence at the Institute for Future Conflict at the Air Force Academy. What are the main ways in which the questions the cadets ask you are different from what you get asked by veterans of our generation (the GWOT generation)? What are the ways the questions are similar?

These kids grew up in an America that was always involved in foreign war. You can tell. Many also come from military families. We’re reading Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell right now, and we spent a good fifteen minutes discussing two diverging definitions of “peace” in it: is it “a hiatus betwixt wars,” as we tend to think of it, or is the real thing more a “millennia of imperishable peace,” which a lot of countries and societies have never known, to include our own? Is such a thing even possible?

The cadets I’ve been charged with teaching are gifted, intellectually curious, practical—every day, they inspire me with their courage and implicit sense of duty, and I try to give them my absolute best, as they deserve. I also can’t help but feel that we’ve failed their generation in some way by giving over to them such a messy and violent world. I don’t think it had to be this way, but I’m also a fool novelist, so who knows.

A piece of advice you’ve given to writers, especially veteran writers, is to remember that “good writing, even writing that’s interested in chronicling a lived experience close to the bones of it all, remembers it’s about bringing others to that place and time.” Are there places and times that are most on your mind as you look towards your next book or the writing you are doing now?

Escaping the tumult of 2025 right now is both a privilege and my professional obligation. I’m working on a book involving a hapless soldier and time travel. Some mornings before work, I’m mired in the particulars of Civil War happenings in 1863. Other mornings I’m figuring out what the hell America in 2150 might resemble. It’s fun. It’s humiliating. It’s writing.

How does that pertain to advice for aspiring writers? I don’t know, maybe just try to remember serious writing that aims for public audience is more an act of communication than expression. That old wisdom from David Foster Wallace has helped me out a few times when I’ve attempted to be too clever or writerly.

Back in 2016, in a reddit interview, you mentioned that you had the “Wheel of Time” series on your top shelf, next to Hemingway and Don Quixote. What’s on your top shelf now?

Full disclosure, my family and I moved to Colorado eight months back and most of my library is still packed up in boxes in the basement. So the top shelf now consists of Lego sets built by my eldest son that he wants to keep from the interests of the dog.

Once I unpack: Conrad’s Lord Jim is a tremendous meditation on bravery and failure, incredibly relevant to the experiences of many GWOT veterans, I think. For Rouenna by Singrid Nunez knocked me sideways, it’s as much about what it is we owe one another as friends, citizens and human beings as it is about the lifelong trauma carried by a nurse who served in Vietnam. And over the Covid summer (five years ago now, somehow?), I participated in A Public Space’s “Tolstoy Together,” which was an online book discussion of War & Peace, led by the novelist Yiyun Li. Tolstoy, man, what a mad, clairvoyant genius. If anyone reading this hasn’t yet sat down with War & Peace, it’s worth the mighty slog, I promise.

I’ll close by reflecting on a quote from the final chapter of Kaboom, when Matt transitions out from the Army and is driving away from his base: “I wanted to feel like a titan who had just dropped a great boulder of burden. Instead, I felt like a naked man locked outside of a clothing store.” Many of us have felt something like this. It might not be standing naked outside a store, but we know that feeling of distance from people around you and have felt the barriers that can separate you from the rest of society, even while at the same time you feel enormously exposed and vulnerable.

One of my motivations in launching Army 250 was to give voice to these kinds of experiences among the military community. But I also wanted to speak to what I see as the civilian corollary to standing naked outside of a clothing store. For those disconnected from the military, interactions with the armed forces can be quite discombobulating. The experiences are much less intense and fraught with far fewer risks than those faced by folks transitioning out, but nonetheless, for most Americans, stepping onto a military installation feels like visiting animals at the zoo. Even just talking about the military can put many Americans immediately into spectator mode.

Instead of feeling naked or like a spectator, we want more Americans to feel at home wherever they are in the military-to-civilian spectrum. We want conversations about the Army (and other services) to be ‘us” conversations and not “them” conversations. One of the most powerful ways to build that sense of connection is through stories that transcend identities of military or civilian and bring us into a shared experience of war and life. Matt Gallagher tells such stories and helps others give voice to such. He is, as he described Tim O’Brien, a clear-eyed chronicler of war; someone we can trust will continue to challenge and entice us to engage with war, the “hard truths about it, messy ruin, dark absurdity, all the rest, too.”

Army 250 is a passion project celebrating the Army’s 250th birthday in 2025. If you enjoyed this piece, please share it with your networks. If you are a new reader, please subscribe below.

Additional Resources:

You can see Matt’s books and other work on his website here.

PLEASED to see that you quoted from my blurb of Daybreak when formulating one of your questions...I appreciate you latching onto it...I dig Matt's work/s.

Great write up Dan. It's all inspiring, and curious.

I'm editing a novel I wrote last year. It's about growing up poor in the south, experiencing the GWOT at a young age and a lot to do with returning from the GWOT at a young age.

Always enjoy your articles.