The Literature of Army Veterans and America's Sense of Self (Preview)

The Soldier's Faith and the Dawn of 20th Century America

This week Army 250 is taking a break from our series on history to drop a short preview of our next series, the Literature of Army Veterans. We’ve covered specific veteran authors at times, such as Edgar Allan Poe and Richard Scarry, but with this new series we will focus on how Army veterans commented on and informed Americans’ sense of self at various points in our history.

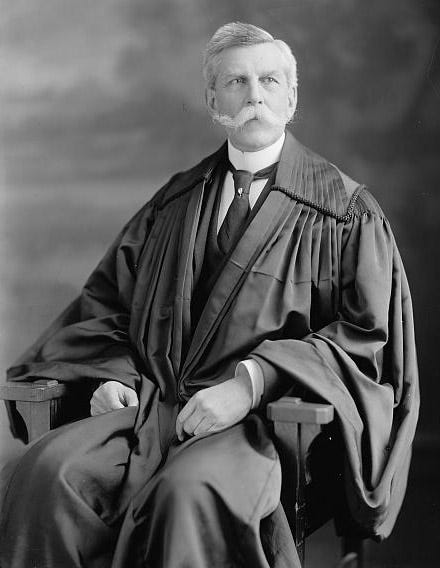

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. Source: Library of Congress.

“[T]he man who commands attention of his fellows is the man of wealth.” This quote could easily be pulled from America in 2025, where a new“money culture”, to borrow from Michael Lewis, seems ascendant. But these words are not of our era. They are from a different time in our nation’s history, the peak of the Gilded Era and the dawn of the 20th century. The author was someone both deeply rooted in specific times (the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Gilded and Progressive Eras for example) and timeless: Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Best known for his influence on American jurisprudence from his time as a justice on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and then the Supreme Court of the United States, Holmes was also an Army veteran and insightful commentator on American society. He was an active voice in many of the most important cultural and political debates of his time. In his speech “The Soldier’s Faith”, delivered on Memorial Day 1895 to the graduating class at Harvard, Holmes critiqued what he saw as weaknesses in contemporary American society, namely its money culture and (illusory) attempts to alleviate suffering, and offered a romantic vision for the necessity of honor and duty, epitomized in the soldier’s willingness to give his life in battle.

The speech both reflects and departs from his legal writing. As John Matteson notes in his book about the battle of Fredericksburg, A Worse Place Than Hell, “[i]n his legal philosophy, Holmes was subtle and nuanced. In his patriotism, he was raw and elemental.” His subtlety and nuance come through in the speech’s critique of those who hold too dogmatic a faith in science, for example, but the bulk of the speech is emotional and spiritual, bold and unapologetic.

He opens with his critique, taking aim at modernity’s glorification of luxury and money and its utopian visions for a world devoid of suffering.

“There are many, poor and rich, who think that love of country is an old wives’ tale, to be replaced by interest in a labor union, or, under the name of cosmopolitanism, by a rootless self-seeking search for a place where the most enjoyment may be had at the least cost.”

Ominously, the nation has been swept up by what he calls “a whole literature of sympathy” that proclaims all pain is evil. Such literature builds on rising confidence that through science and reason, humans can overcome all of their failings and realize a world free of pain; a world free of the irrationalities of faith, nature, and passion.

“Even science has had its part in the tendencies which we observe. It has shaken established religion in the minds of very many. It has pursued analysis until at last this thrilling world of colors and passions and sounds has seemed fatally to resolve itself into one vast network of vibrations endlessly weaving an aimless web, and the rainbow flush of cathedral windows, which once to enraptured eyes appeared the very smile of God, fades slowly out into the pale irony of the void.”

And yet, while Holmes can imagine a future where science might realize this promise, it appears far, far away. For the foreseeable future, “struggle for life is the order of the world” as he sees it. And in this struggle, war looms large.

“Now, at least, and perhaps as long as man dwells upon the globe, his destiny is battle, and he has to take the chances of war. If it is our business to fight, the book for the army is a war song, not a hospital sketch.”

For what the nation needs now, and will always need, Holmes argues, is honor. Modernity makes false promises that honor can be attained through wealth or well-intentioned attempts to end suffering, when honor must involve pain and sacrifice, a “splendid carelessness for life”. To accept anything less would be as if “we are trying to steal the good will without the responsibilities of the place.”

In the pursuit of honor, we must then embrace the soldier’s faith.

“I do not know what is true. I do not know the meaning of the universe. But in the midst of doubt, in the collapse of creeds, there is one thing I do not doubt, that no man who lives in the same world with most of us can doubt, and that is that the faith is true and adorable which leads a soldier to throw away his life in obedience to a blindly accepted duty, in a cause which he little understands, in a plan of campaign of which he has little notion, under tactics of which he does not see the use.”

It is this faith which grounds us in humility, knowing as we do the “vicissitudes of terror and triumph in war”, and yet also fills us with the most transcendent sense of purpose and confidence. As Holmes puts it, “…you know that man has in him that unspeakable somewhat which makes him capable of miracle, able to lift himself by the might of his own soul, unaided, able to face annihilation for a blind belief.”

Holmes does not hope for war and in fact he says “I hope it may be long before we are called again to sit at that master’s feet.” But we need these sorts of crucibles to experience the true meaning of honor. We need them in “this snug, oversafe corner of the world” and “in this time of individualist negations, with its literature of French and American humor, revolting at discipline, loving fleshpots, and denying that anything is worthy of reverence”. We need them at all times, Holmes tells us, as this is the only way to serve as witness to that which is beyond our normal comprehension.

“For high and dangerous action teaches us to believe as right beyond dispute things for which our doubting minds are slow to find words of proof. Out of heroism grows faith in the worth of heroism.”

Holmes closes by acknowledging his time to take to the field has passed. He has no regrets here. He goes forward knowing “[w]e have shared the incommunicable experience of war; we have felt, we still feel, the passion of life to its top.”

Holmes’s speech was a defense of heroism in an unheroic era. America in 1895 was engulfed in conflict and filled with competing pulls of exuberant confidence in the future and deep cynicism. Populist fervor was sweeping the nation; Reconstruction had given way to entrenched segregation in the South; and new industry and technology simultaneously uplifted and terrified the nation. As Richard White writes in his history of Reconstruction and the Gilded Era, “[t]he century was closing with a mad and seemingly destructive rush.” In this context, The Soldier’s Faith can seem out of place, a romantic myth more appropriate for fairy tales than for real life.

Yet, this period also saw a new rush of patriotic initiatives. Reciting a pledge of allegiance at school became a new custom in 1892, for example. Holmes thus spoke to something moving in American culture, a spirit that was later personified (to a great extent) by Teddy Roosevelt (who as President appointed Holmes to the Supreme Court)

Holmes was no idealist. He was first wounded in October 1861, shot in the chest at Balls’s Bluff. He was shot in the neck at Antietam in 1862. He fought in some of the most hellacious battles of the Civil War in 1863 and 1864. He saw the worst of human instincts and forever kept a skeptical view towards utopian ideas. Nor did display the ebullience we associate with Teddy Roosevelt. But there was something profound in his disposition and outlook on life.

As he told a gathering of veterans in 1884, “our hearts were touched with fire”. A decade later, that fire still burned bright in his Harvard speech. Its light would help guide Americans, however imperfectly, towards a new sense of self as the nation entered the 20th century.

Additional Resources:

Holmes is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. You can learn more about his gravesite here.

You can also learn more about Holmes at the Supreme Court Historical Society’s website here.

Be Part of Army 250

If you’d like to write a newsletter post, share an educational resource about the Army, or lift up an opportunity for people to connect with the Army (e.g., an event, story, etc.), please contact Dan (dan@army250.us).

Books referenced in this post include:

Budiansky, Stephen. (2019). Oliver Wendell Holmes: A Life in War, Law, and Ideas. First edition. New York, W.W. Norton & Company.

Matteson, John. (2021). A Worse Place Than Hell: How the Civil War Battle of Fredericksburg Changed a Nation. First edition. New York, W.W. Norton & Company.

White, Richard. (2017). The Republic For Which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896. New York, Oxford University Press.

Wow… so glad I found this account. Fantastic article and excited to keep reading this new series.