The Luck of Richard Scarry

This week we hear from guest author, Huck Scarry

This week we feature our first guest author. Huck Scarry is an author and illustrator of children’s books. Huck is also the son of Richard Scarry, the creator, author, and artist behind Busy, Busy, World and Cars And Trucks And Things That Go, and many other of the most widely-read children’s books in history. Richard Scarry produced over 300 books which have sold over 160 million copies around the world.

Richard Scarry was also an Army veteran. His story exemplifies the ways the Army has influenced, and been influenced by, aspects of American life far beyond what is typically read in military histories. Richard Scarry’s time in the Army was formative for him as an individual, and at the same time, part of a much wider, national story of service.

I grew up reading Richard Scarry’s books and I now read them to my 3-year-old son. It gives me great pleasure, then, to feature Huck this week. I’m grateful for his collaboration and support for Army 250.

The Luck of Richard Scarry

My father, Richard Scarry, was born in 1919, in Boston, Massachusetts. Young Richard was a lively boy, but was never a very good pupil in school. He really only liked doing one thing: drawing.

Richard’s mother recognised his talent, and enrolled him at courses at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. She would bring him there on Saturday mornings, and he would practice his talent, making drawings of plaster casts of statues.

Richard’s father owned a large clothing store in Boston, called Scarry’s. He hoped that Richard might one day take an interest in the store. But Richard was not particularly fond of anything to do with numbers or business, and his grades showed it. Richard even had to repeat his last year at High School. Exasperated with what to do with his son, his father finally agreed to let him study Art at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. But he warned his son of a certain destiny of cold, damp attics and a diet of spaghetti!

Richard thrived at the Museum School. This was exactly what he loved to do, and which he could do well. But alas, even here, he was unable to graduate, for the Second World War got in the way. The US declared war on Japan in 1942, and Richard was quickly enlisted into the Army.

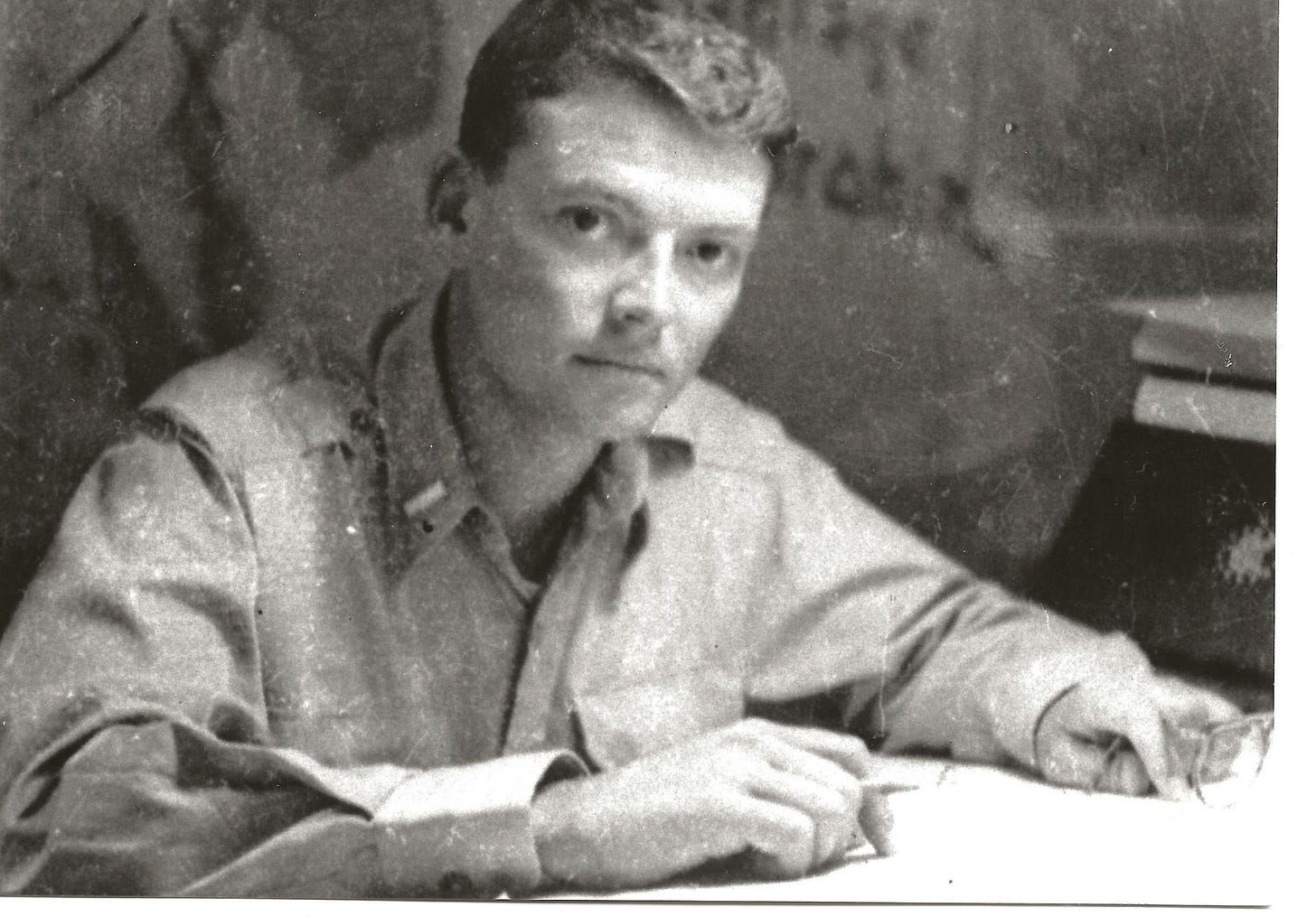

Richad Scarry, Spring 1944, in Ain-el-Turk, near Oman, Algeria, where he was based at that time with Allied Forces Headquarters. (Source: Huck Scarry.)

On the entrance-questionnaire, there was a place where one could list one’s professional qualifications as well as interests. Richard wrote down “Artist”. With that, he was sent-off to Radio Repair School at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. He hated it. He had no interest in radios, and no talent in repairing anything! But Luck smiled at him at Fort Monmouth. He was ordered to report to the Major’s office. He wondered what it was that he could possibly have done wrong.

To his surprise, the Major was holding Richard’s questionnaire. “I see you’re an artist, Scarry. Can you paint letters… A,B,C… that sort of thing?” “Yes indeed, sir.” Richard replied. And so Richard was given a lot of black paint, and a lot of silver paint and was told to repaint the fort’s entrance sign in silver letters on a black background. The surface of the sign was huge: some 30 feet long, and it was to read:

WELCOME TO THE SEVENTH ENGINEERS OF FORT MONMOUTH, NEW JERSEY, U.S.A.

Richard was in luck: it would take weeks for him to finish painting such a big sign! And here was a chance to show a bit of what he could do.

About this time, Richard applied to Army Administration Officer Candidate School. He was accepted, and in just three months he was a 2nd Lieutenant. He was furthermore assigned to Special Services: the branch of the Army dedicated to boosting the morale of the fighting troops. Richard, among other things, was trained here in the techniques of sending news and information to the soldiers overseas.

Richard’s good luck, though, was only beginning: He was told that Army Headquarters in North Africa needed an art director: “Pack your gear and get ready to go!”

In Algiers, at Allied Headquarters, Richard was given an office. From a Colonel: his orders. “You are supposed to tell the troops why they are fighting and send them news from home!” “How are we supposed to to that, sir?” asked Richard. “By post!” snapped the Colonel, and left him to it.

Poor Richard hadn’t a clue what to do, nor where to begin… he hadn’t even written a single letter home yet! But then he got an idea: He asked that a copy of TIME magazine be delivered to his office each week. As the first copies arrived on his desk, he read through the news, both international and domestic, and reduced it into terms, length and language that would be easy and interesting for any soldier to read. He added illustrations and maps. These news fliers were then printed on a simple mimeograph machine and sent off to soldiers stationed all over North Africa. And on he went, preparing manuals and guidebooks for soldiers arriving from the States.

Richard Scarry, 1945, Allied Headquarters, Caserta, Italy. (Source: Huck Scarry.)

I could be wrong, but I have the distinct feeling that Richard Scarry’s time in the US Army was the seed which made him the author and illustrator that he later became. What he explained in a simple way to soldiers, he would equally later explain sometimes very complex things to small children. What Do People Do All Day? (1968) and Great Big Air Book (1971) are two masterpieces of this rare talent of Richard’s.

The War over, Richard returned to the States with the rank of Captain. He went to New York to try his luck at advertising illustration, with modest success. Happily, he was put in touch with an agent who had the remarkable idea to ask Richard make some sample drawings for children’s books. When Richard was ready, his agent secured an appointment for him at Artists and Writers’ Guild, a small editorial branch of Western Printing Company.

Artists and Writers’ Guild had started a series of handsome storybooks bound with a distinctive golden binding. They were called Little Golden Books. They only cost 25 cents.

The editors liked Richard’s samples enough to commission him with a contract for four storybooks, and paid him a monthly income of $400.-, which in those days, you could live on. This was in 1948. In 1949, Richard’s first illustrated book came out: Two Little Miners , written by Margaret Wise Brown. Richard was on his way. The rest is history.

***

My father always liked to give advice. He was constantly telling people, including myself, of course, what they ought to do… wagging a knowing finger in the air to make his point. My mother often joked that he should have been a preacher!

There was one bit of advice that my father regularly repeated: “ You can have bad luck, and you can have good luck___but in the end, you make your own luck.”

Huck Scarry

I would like to acknowledge and thank the authors of my father’s biography: The Busy, Busy World of Richard Scarry published by Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1997, written by Walter Retan and Ole Risom, who were respectively my father’s editor and art director at Random House Children’s Books, and who were his friends.

Additional Resources:

For more on Richard Scarry, you can visit this site: https://www.richardscarry.com/.

Be Part of Army 250

If you’d like to write a newsletter post, share an educational resource about the Army, or lift up an opportunity for people to connect with the Army (e.g., an event, story, etc.), please contact Dan (dan@army250.us).