"the story part of my generation"

The Literature of Army Writers and America's Sense of Self. Part VII: F. Scott Fitzgerald

“the sentimental person thinks things will last—the romantic person has a desperate confidence that they won’t.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald was a romantic, perhaps the romantic, in early 20th century America.1 He gave name to the Jazz Age and through his writing captured interwar America in a way unlike any other writer: its beauty and passion, excess and superficiality, boundless optimism and deep-seated fears. He set out, in his own words, to capture “the story part of my generation in America” and succeeded far beyond anything even he could have imagined.

Millions still read his works every year. The Great Gatsby alone has sold more than 25 million copies, been translated into more than 40 languages, and produced four different cinematic versions (most recently in 2013). Though very much a voice for his generation, Fitzgerald still speaks to Americans of all ages today. As leading Fitzgerald scholar James L. W. West III put it, with the The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald produced "a national scripture. It embodies the American spirit, the American will to reinvent oneself."

Yet as talented as he was, Fitzgerald’s success and impact came only through his partnership with his wife Zelda. And it was the U.S. Army that made this unique union possible.2

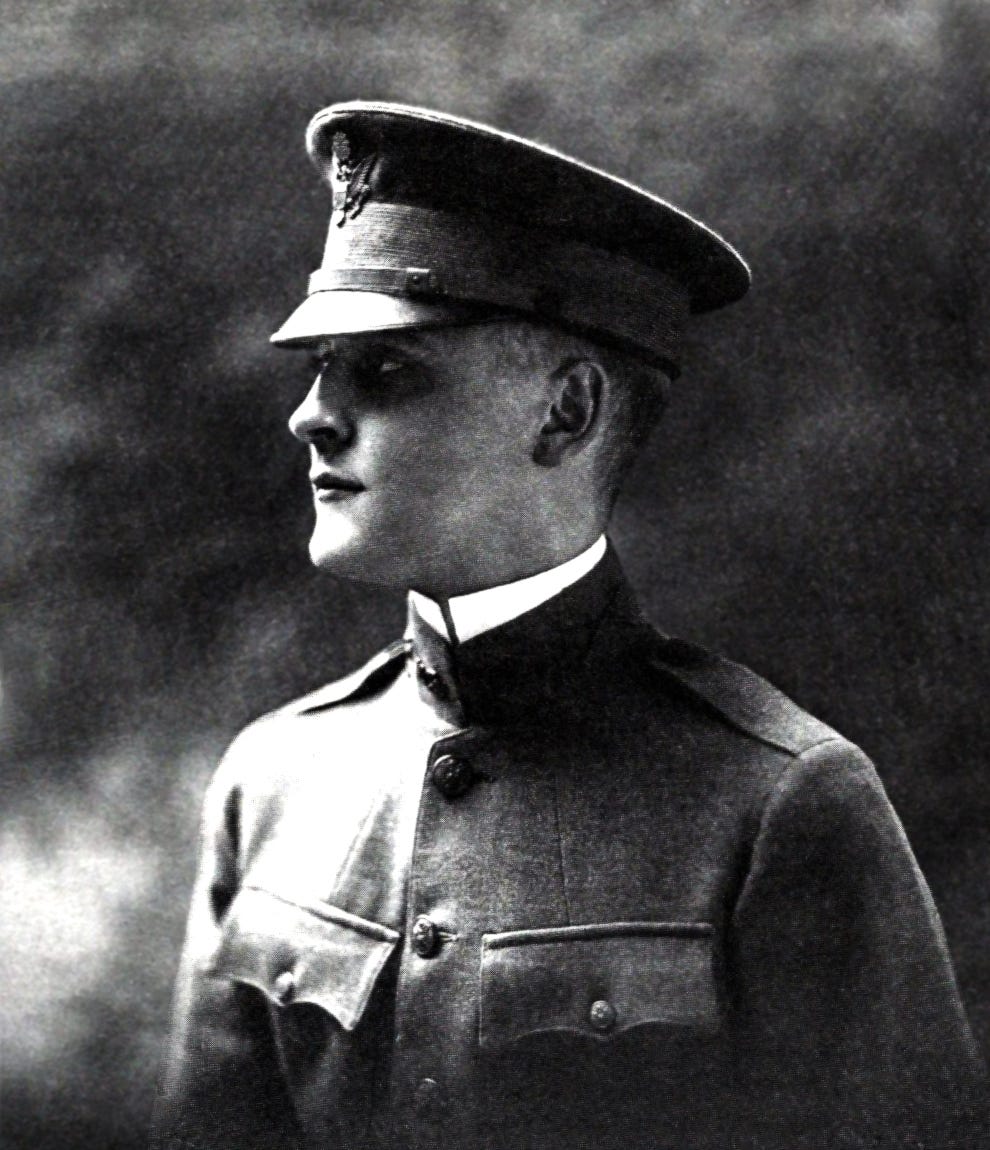

F. Scott Fitzgerald the soldier is not a well-known story. His military experiences show up only occasionally in his writing. It was his friends and contemporaries, most notably Ernest Hemingway, who wrote the great American war novels of this period.3 But Fitzgerald’s time in the Army proved critical as it brought him to a country club in Montgomery, Alabama where he met one Zelda Sayre.

F.Scott Fitzgerald in his Army uniform. Source: F. Scott Fitzgerald Archives

An Impediment to His Writing

Dreams of glory and romantic notions of duty moved Fitzgerald to volunteer for the Army soon after America entered the war in 1917.4 Though he initially considered Army aviation, as it seemed to him the modern equivalent to the cavalry in the Civil War, he ultimately chose the infantry. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the infantry October 26, 1917 and after outfitting himself at Brooks Brothers, reported for training at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.5

The Army did not come as naturally as writing did to Fitzgerald. To put it bluntly, he was a pretty poor soldier. He had a habit of sleeping during training, which is bad enough in any situation, but even worse when the trainer you fall asleep on is Dwight Eisenhower, future Supreme Allied Commander. It’s unlikely Ike’s opinion mattered too much to Fitzgerald, however, as, in the words of his biographer Matthew Bruccoli, “he regarded the army as an impediment to his writing.” And write he did.

“Every evening, concealing my pad behind Small Problems for Infantry, I wrote paragraph after paragraph on a somewhat edited history of me and my imagination.”6 Fitzgerald felt such urgency to write, perhaps on one level out of a desire to escape the Army, but more meaningfully, because he felt his perspective on life would change so greatly due to the war that he had to capture how he felt now, before he shipped out. “I’ve got to write now, for when the war’s over I won’t be able to see these things as important—even now they are fading out against the back-ground of the map of Europe.”

During his Army training, Fitzgerald produced a full novel, “The Romantic Egotist”, largely based on his own life. Publishers rejected his submission, but this writing experience, scribbled while pretending to learn small unit tactics, proved enormously influential on his career. The rejected novel formed the basis for his breakout book, This Side of Paradise, and in the process of corresponding with Scribners, he connected with Maxwell Perkins, an editor who went on to champion Fitzgerald and propel him to greater literary acclaim.

But the most important moment from his time in the Army was a dance in July 1918 at the Country Club of Montgomery, Alabama, where he met Zelda Sayre. Zelda wrote of this moment in her book Save Me the Waltz: “There seemed to be some heavenly support beneath his shoulder blades that lifted his feet from the ground in ecstatic suspension, as if he secretly enjoyed the ability to fly but was walking as a compromise to convention.” Though they both dated other people in the following months, the chance encounter lit a spark never went out.

Zelda Fitzgerald. Source: Library of Congress.

A few months after meeting Zelda, Fitzgerald shipped north, his unit set to deploy to France. But on November 11, the warring parties signed an armistice and the deployment was canceled. He was disappointed to not go overseas.

Although Fitzgerald only had a few months left in uniform, he continued his pattern of less-than-soldierly behavior. He had to be confined to a base, Camp Mills, for example, to keep out of trouble, and he briefly went AWOL (absent without leave) to New York City when his unit was ordered back to Montgomery. Fitzgerald and the Army finally parted ways in 1919 when he was discharged.

Finding the Right Side of Paradise

Fitzgerald’s post-Army experience was challenging. He was working a job he didn’t care for at an advertising agency; his relationship with Zelda was rocky; and he felt like the literary future he dreamed of was slipping out of his grasp. So he moved back home to Minnesota.

Remarkably, this did the trick. Within a short period of time he produced This Side of Paradise, a novel based largely on the draft “The Romantic Egotist”. Scribners accepted the book and it proved a hit: its first year (1920) it sold more than 50,000 copies and made him a national sensation. During this same time period, Zelda agreed to marry Fitzgerald and the two wed in April 1920, a week after his novel hit bookshelves for the first time.

From here it was an epic and chaotic journey. Their only child, Frances, was born in 1921; they lived in Paris and took part in Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast; The Great Gatsby was published in 1925; and so much more.7 The full weight of artistic output and the total mass of his and Zelda’s unique partnership are beyond the scope of this article to describe, but it’s fair to say they were among the most influential writers and artists of their generation. The New York Times obituary for F. Scott Fitzgerald, who died in December 1940, captures this enormous, if tragic, influence:

Mr. Fitzgerald in his life and writings epitomized "all the sad young men" of the post-war generation. With the skill of a reporter and ability of an artist he captured the essence of a period when flappers and gin and "the beautiful and the damned" were the symbols of the carefree madness of an age.

Some of those sad young men that appear in his stories can be traced to Fitzgerald’s time in the Army. In The Beautiful and Damned, published in 1922, the protagonist, Anthony Patch trains at an Army base in Georgia and becomes involved with a local girl—it does not go well for Anthony. Similarly, Jay Gatsby is an Army veteran who fought in the Argonne offensive of World War I and won a medal when his unit was surrounded by the Germans, a story Fitzgerald based on “The Lost Battalion” of the American Expeditionary Force. But his genius lay not in bringing readers to battlefield, but in capturing the worlds veterans of the Great war returned to.

Ineffable Symbols

In his short story, The Offshore Pirate, published in 1920, we find perhaps the most revealing anecdote about Fitzgerald’s relationship to the Army, and to America more broadly. In this story, we hear of a young man who served in the military during World War I, but as a band leader, far from the front lines. This young man tells us: “It was not so bad—except that when the infantry came limping back from the trenches he wanted to be one of them. The sweat and mud they wore seemed only one of those ineffable symbols of aristocracy that were forever eluding him.”

Those ineffable symbols are familiar to anyone who has served in the military. Veteran Ben Kesling writes about serving in war as the crucible through which soldiers become “members of the club”.8 For Fitzgerald, “the club” is just part of the story however; it is not just in reference to other veterans that he feels inadequate, but to the tranche in society, the aristocracy, whose acceptance he yearned for, yet felt he never secured.

We all have our own ineffable symbols. Much of life is in how we deal with these symbols, the ones we give weight to, the ones we cast aside, and the ones we come to terms with. This process, of interpretation and attempts at reinvention, is at the heart of Fitzgerald’s work, which is why his stories still ring true long after the music stopped for the Jazz Age.

Author’s Note: I’d like to thank Jim West, a retired English professor at Penn State University, for his help developing and reviewing this newsletter. I’m grateful that he responded to a cold email and served as a terrific resource for this post.

Lifting up Army writers on Substack

This week we look highlight another Army writer,

. Rob served in the Army for nearly 30 years and now runs an extensive coaching and leader development company. He writes on personal leadership and the state of leadership in the workplace today, provides tutorials and lessons for leader development, and offers a range of resources for how to lead yourself and any team.Additional Resources:

You can learn more about F. Scott Fitzgerald at the Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum here.

Army veteran Colin Halloran wrote an interesting article on Fitzgerald’s “Crack-Up Essays”, that were published after Fitzgerald’s death.

Be Part of Army 250

If you’d like to write a newsletter post, share an educational resource about the Army, or lift up an opportunity for people to connect with the Army (e.g., an event, story, etc.), please contact Dan (dan@army250.us).

The quote about difference between a romantic and a sentimental person is from This Side of Paradise. Fitzgerald’s full name was Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald, named after his distant cousin, Francis Scott Key, author of the “Star-Spangled Banner”.

There have been many books, articles, and other commentaries on F. Scott and Zelda’s marriage and family life. That is not a focus with this article, but you can see one example here in a piece from one of their grandchildren, Eleanor Lanahan.

Fitzgerald and Hemingway had a complex relationship that unfortunately fell into disarray; they were not speaking at the time of Fitzgerald’s death in 1940.

Bruccoli, Matthew J. (2002). Some Sort of Epic Grandeur: The Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Columbia, South Carolina, University of South Carolina Press. Bruccoli’s biography provides most of the quotes and factual information recounted in this article. In this book, Bruccoli recounts a fascinating plan where Fitzgerald was to accompany Father S.W. Fay on a covert mission to strengthen Catholics in Russia during World War II. They were to use the Red Cross as cover for this covert operation. Nothing came of this, but a letter sent to Fitzgerald by Father Fay underscores the appeal that glory (and maybe intrigue) held for a young Fitzgerald: “There is no salary for any of us; they expect us to take it out in glory, and really there will be glory enough if we manage to do what I hope we will.”

As a former infantry officer, I find it interesting that Fitzgerald went to Brooks Brothers for his uniform. It’s a great reminder of the extent to which officers—and soldiers more generally—used to purchase their own gear. This still goes on to a limited extent, though Brooks Brothers is a far cry from the Ranger Joes I went to before Ranger School.

Another interesting tie-in between Fitzgerald and the Army is that the military helped increase sales of The Great Gatsby. The novel was selected to be included in a book collection distributed to soldiers deployed abroad during World War II.

Kesling, Ben. (2022). Bravo Company: An Afghanistan Deployment and Its Aftermath. New York, Harry N. Abrams.