The Unnecessary Things We Carry

The Literature of Army Veterans and America's Sense of Self. Part IV: Tim O'Brien

“Forty-three years old, and the war occurred half a lifetime ago, and yet the remembering makes it now. And sometimes remembering will lead to a story, which makes it forever.”

The unnecessary things we carry reveal our soul. Weighed down with weapons, ammunition, communications and first aid equipment, maps, ponchos, extra socks, matches, and whatever else might carve out the slightest advantage over the enemy, soldiers nevertheless always pack more. For Lieutenant Cross, it was letters from a girl he loved, Martha, who did not share the flame; for Kiowa it was the New Testament; and Kiley, comic books. On top, we all carry memories: ones that restore—the last kiss before deployment—and ones that haunt—the image of Ted Lavender shot in the head. All these extra pieces, the luggage not made for war, tell stories about us, our wars, and if we are so lucky, the journey home.

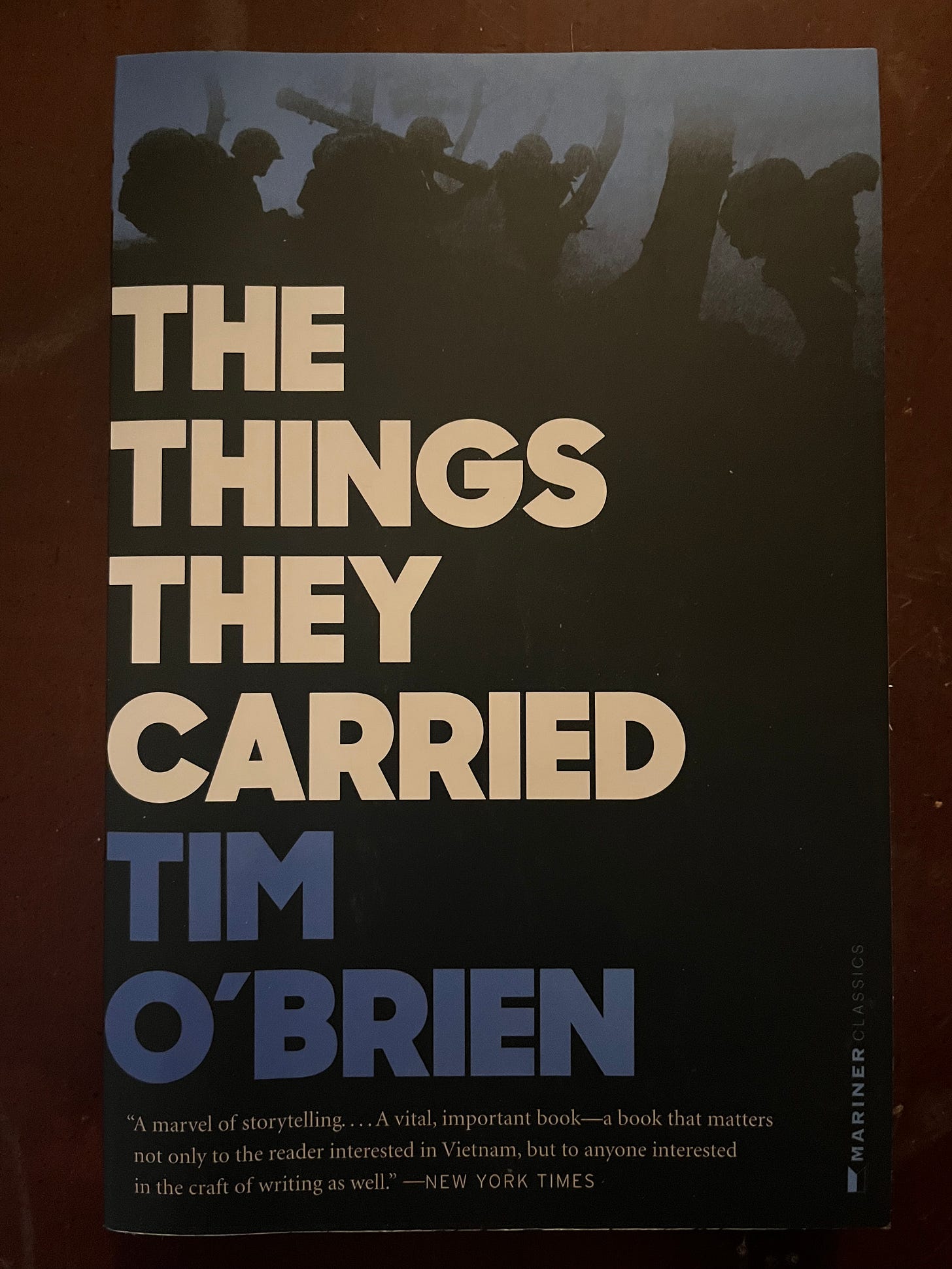

No one has captured these stories the way Army veteran Tim O’Brien did with The Things They Carried. First published in 1990, it received immediate recognition: it was a finalist for the 1990 National Book Critics Circle Award and the Pulitzer Prize in 1991. It went on to become an essential piece of war literature, selling millions of copies worldwide, earning a place on multiple “must read” lists, and taking hold in high schools and higher education.

The book is a blend of biography and fiction. Tim O’Brien was drafted and served one tour in Vietnam from 1969 to 1970 with the 46th Infantry. He was injured in a grenade attack and received a Purple Heart. In The Things They Carried, O’Brien serves as the narrator and the stories revolve around a platoon of soldiers and their experiences in war and back home. Above all, however, it is about storytelling itself.

Source: Author’s photo.

“In a true war story, if there's a moral at all, it's like the thread that makes the cloth. You can't tease it out. You can't extract the meaning without unraveling the deeper meaning. And in the end, really, there's nothing much to say about a true war story, except maybe ‘Oh.’”

The Things They Carried was not O’Brien’s first book. He published a memoir, If I Die in a Combat Zone: Box Me Up and Ship Me Home, in 1973, and his novel, Going After Cacciato, also set in Vietnam, won the National Book Award in 1979. Yet The Things They Carried resonated with the American public in a unique and powerful way. As Robert Harris wrote in the New York Times book review, “By moving beyond the horror of the fighting to examine with sensitivity and insight the nature of courage and fear, by questioning the role that imagination plays in helping to form our memories and our own versions of truth, he places ''The Things They Carried'' high up on the list of best fiction about any war.”

The book arrived at a time of transition for America and its relationship with the Vietnam War. A year after the book’s publication, in March 1991, following victory in the Gulf War, President George H.W. Bush memorably said the nation had finally “kicked the Vietnam syndrome once and for all.” The speed and magnitude of victory demonstrated, it seemed, that the military had transformed from an institution in crisis post-Vietnam to the most devastating military in the world, generations ahead of any adversary on the field of battle. (This journey was chronicled in books such as James Kitfield’s Prodigal Soldiers, published in 1997.)

In parallel, American society was undergoing a transformation with respect to the Vietnam War. The war had been incredibly divisive. Significant portions of those opposed to the war had made few, if any, distinctions between the war and the service members who fought it.1 Returning soldiers were often met with derision; government support systems for transitioning veterans were weak or nonexistent; and popular media fueled misperceptions of veterans as ticking time bombs.2 As a consequence, many veterans opted to take all that they carried from the war and bury it deep inside.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, the nation started a process of healing. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial (“The Wall”) was dedicated in 1982. Peer support networks for veterans expanded and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) began to look more seriously at post-traumatic stress disorder. There remained deep scars from the war, both at the individual level and as a nation, but there was a new willingness to talk about the war and engage with the full complexity and humanity of its veterans (and their families).3

The Things They Carried spoke to this moment. As the National Endowment for the Arts put it in a reading guide for the book, “There may be no better bridge across these twin divides [between Americans regarding the Vietnam War] than Tim O'Brien's novel in stories The Things They Carried.” Its importance has only grown in time. As noted by Steven Kurutz in the Wall Street Journal in 2010, “[o]f the classic works of Vietnam literature, many published in the '70s when the war was fresh, it is Mr. O'Brien's "The Things They Carried" that seems to resonate most lastingly.”

Tim O’Brien. Source: Library of Congress.

Yet, it is not quite right to think of the book as a war book. For O’Brien, it was much more about the people and about the role of storytelling in the human experience: “I've never thought of it, really, that way [as a war book] in my heart. Even when I was writing it, it seemed to be a book about storytelling and the burdens we all accumulate through our lives”. Its power comes not from the battles it chronicles; in fact, as is often noted, the enemy is rarely physically present. Power comes from the soldiers and their stories.

Mark Fossie sneaking his hometown sweetheart Mary Anne Bell into Vietnam and watching her transform into a battle-hardened warrior.

Tim O’Brien (the narrator) talking with his daughter, “‘Daddy, tell the truth,’ Kathleen can say, ‘did you ever kill anybody?’ And I can say, honestly, ‘Of course not.’ Or I can say, honestly, ‘Yes.’”.

Lieutenant Cross trying to bury his guilt in the ground: “All he could do was dig. He used his entrenching tool like an ax, slashing, feeling both love and hate, and then later, when it was full dark, he sat at the bottom of his foxhole and wept.”

However distant the setting might seem to the reader, there is an intense relatability with each vignette. O’Brien’s goal, as he relayed to a listener on NPR, was first to make the stories feel personal for the reader: “to hit the human heart and the tear ducts and the nape of the neck and to make a person feel something about the characters are going through and to experience the moral paradoxes and struggles of being human.” We might not know what the weight of an M-60 feels like or what a P-38 is used for, but we all deal with love and death, guilt, regret, and joy; we all wrestle with our angels and demons; and we all carry ghosts.

“But like the ghosts of Vietnam, all I need do is, you know, close my eyes a moment and there he [O’Brien’s father, who had passed away] is throwing me a baseball. And there's something about carrying the image of him, the symbol, the emblem of carrying that, at least in my experience, is pretty important to being human, I mean.”

Some ghosts stay with us forever. My friend Todd was killed in Afghanistan in 2010, the same year I was there. Just two years prior, we had stood in the same squad at Infantry Officer Basic Course as one of our noncommissioned officers told us, “gentlemen, look to your left and to your right, one of you will fall in battle.” A line straight out of a movie I thought at the time. But it turned out it came from Hell not Hollywood. Still today, I can close my eyes and see Todd—hunched over a map out in the field or standing with his wife and young daughter in a parking lot at Fort Benning.

Some ghosts stay only for a certain time. After my deployment, I carried an unexpected ghost: guilt. I had deployed as an infantryman, but assigned to a training mission. I never had to fire on the enemy nor was I ever directly engaged. Threats orbited around me, the standard ones anyone might face: IEDs or VBIEDs when you went out the gate or the possibility that terrorists had infiltrated the partner local forces. But measured against what many of my peers faced, what Todd faced, my war was safe.

For several years after I returned home, and even after I left the Army, I avoided conversations about the wars and national security. What right did I have to comment or weigh in on such things, when so many others had given so much more than me? Who was I to have an opinion about foreign policy when it would be other men and women, not me, who would bear whatever risks our nation asked of them as a result? Such thoughts still show up every now and them, but over time, this ghost quieted, and at some point, left.

Ghosts can be good. I’m grateful and honored to carry Todd, and others who fell in war, with me. I’m grateful too, in a different way, for the ghost of guilt. Wrestling with this ghost brought me closer to my faith, closer to God. Our ghosts, our stories, they can help us find ourselves.

That is one of the enduring lessons of The Things They Carried. In “The Lives of the Dead”, O’Brien writes, “But this too is true: stories can save us.”

Lifting up Army writers on Substack

This week we look highlight two more Army writers on Substack.

Former paratrooper Mark Delaney writes The Veteran Professional. This is a publication dedicated to helping veterans successfully transition out of the military into a thriving career and life. Forged out of his own experience, Mark helps veterans learn how to chart their own path.

Retired Special Forces soldier

writes Mind of Things. In this publication, Justin analyzes current events related to defense, technology, strategy, and the economy. He also shares his perspective on books, parenting, and a range of other topics.

Additional Resources:

Tim O’Brien became a father in 2003. He took an extended break from writing and then in 2019, published Dad's Maybe Book. We get to see O’Brien, whom we met as a young man in the jungles of Vietnam, as a father clearly in love with his sons and with being a father.

Be Part of Army 250

If you’d like to write a newsletter post, share an educational resource about the Army, or lift up an opportunity for people to connect with the Army (e.g., an event, story, etc.), please contact Dan (dan@army250.us).

At the end of the Carter Administration, the VA commissioned a study of attitudes towards Vietnam veterans. After interviewing thousands of veterans and non-veterans, the researchers released a report called Myths and Realities: A Study of Attitudes Toward Vietnam Era Veterans that found most Americans expressed warm sentiments towards those who had served in the war and that most Vietnam veterans expressed pride regarding their service. Unfortunately, the transition experience for many veterans was not characterized by these themes (warmth and pride).

The narrative of the “violent veteran” was not unique to the Vietnam War. Versions of this narrative have shown up going back to the start of recorded history. It continues to stalk veterans today.

The United States normalized diplomatic relations with Vietnam in 1995.

Great post, Dan. I wrote down the title for a future read.